Sometimes, the best way to perceive the nature of a thing is to place it in contrast to a radically different object. Jean Renoir adapts Hans Christian Anderson’s fairy tale in such a way as to highlight the harsh realities of poverty. He achieves his purpose through a sharp juxtaposition of opposites.

In the 33-minute film’s first half, a figure that appears only in shadow forces the poor match girl, Karen, out of her shack and into the blustery night to sell her wares. As she walks through the town, Renoir employs a wide shot followed by a medium shot. People hustle by her as she spins right and left to catch their attention. The movement looks something like a companionless dance, graceful and fluid yet empty. Furthermore, not a single person looks at her until she stops, worn out and depressed from her lack of success.

When a man in need of matches sees her, a glimmer of hope lights the film. But some friends quickly usher him into a nearby restaurant. Just before, she had peered through the window of a car to get a better look at his friends. After the man enters the restaurant, she presses her nose to the window, an outsider to the comfortable world within. Two boys also see her, but only as a target for their snowballs.

When she finally shuffles away from the restaurant, a policeman takes notice, and they spend a few minutes looking in a toy store window together, admiring a collection of figurines in a miniature town filled with joy and peace and order. The encounter is pleasant, but Karen and the policeman have something in common—they both stand outside that wonderful world in the toy store window. When she departs, she can’t bring herself to go home without a sale. So she sits under a lamp in the snow and lights matches to keep warm. Her grueling world offers her no comfort, no solace, and no justice.

At this point, Karen’s hunger and chill lead her to hallucinate that she is in a toy store where everything is life size. Dolls, a ballerina, and a giant beach ball populate this strange place. Renoir blurs the image during the transition, visually indicating a movement away from the harsh realism of the film’s first half.

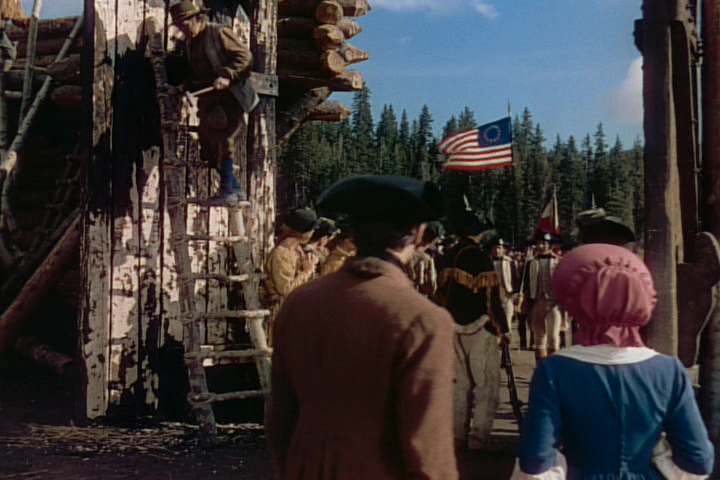

In the store, Karen finds a jack-in-the-box who happens to be the same policeman she had seen on the street. She also spies out the commanding officer of a group of toy soldiers, the same man who needed matches, the same man who held with him the promise of taking her to another kind of world. She runs to him, where he declares his love for her and provides her with a table full of food. Her dreams are coming true.

When the jack-in-the-box approaches them and identifies himself as Death, the officer and Karen jump on a horse and ride into the heavens, hoping that there they will escape. But Death finds them even there. When Death finally lays a lifeless Karen under a cross, the symbol of suffering morphs into a flowering bush. As the petals drop on her dead face, Renoir brings us back to reality, snowflakes falling instead of petals. No one knows of the beautiful moments she had in her last bits of consciousness, seeing only the foolishness of keeping warm with matches.

The abrupt shift from the vision back to reality has the effect of highlighting the painful realities of Karen’s poverty. It’s in the contrast with fantasy that we see the reality clearly, especially because reality actually breaks into Karen’s fantasy and ends it. Renoir is kind to Karen in that final moment, though, closing the film with an out-of-focus close-up of her face. Renoir reminds us of her fantastical vision of a world that, at least for a moment, carried with it some measure of hope. The tragedy of the film is that people like Karen have no hope of elevating their circumstances. But the beautiful desire for something better—for joy and peace and justice—that lies in the most desperate of hearts serves to ignite in us a glimmer of hope as well.