Jia Zhangke’s 20-minute short film, Cry Me a River (which you can find as an extra on the Region 1 release of Jia’s feature 24 City), follows four friends in their late twenties (two men and two women) who have reunited to attend a dinner party in honor of their former professor. Jia’s camera tracks their movements over two days—playing basketball, revisiting old haunts, touring the city by boat and on foot, and of course, attending the dinner that’s brought them back together.

The meeting and meal with the professor takes place about one third of the way through the film, and this sequence, in which Jia uses only three shots, communicates volumes about the director’s concerns in the film as a whole, and also illustrates with striking clarity and efficiency why I appreciate his work so much.

Immediately following a brief tracking shot of the four friends walking to the dinner, Jia brings us directly into the dinner scene in the first of three shots at this location. The edit into this shot provides continuity with the previous shot in its focus on the four main characters of the film. However, it contrasts strongly with what has gone before in a number of ways: the stationary, rather than tracking, camera; the friends seated and still rather than walking; and the bright and colorful indoor setting rather than the drab and gray outdoor location.

This first shot (above) lasts for nearly three minutes, with the camera sitting stationary at eye level. Notice the modern looking dining table, the trendy and/or Western clothes worn by the attendees, the sleek glass—both in the open doors behind the table and the shelving or window in the foreground. The modern world dominates this shot, which is appropriate for what is, outside the professor, a crowd of twenty-somethings. The conversation tracks with the modern look of the shot, with the four friends discussing investments, economics, and the difficulty of survival in a newly westernized China.

After a man comes to pay their travel expenses—another reveal of their financial hardships—the others in the group (who had been standing out on the deck behind the table) file in to take their seats. With the group now gathered around the table, the professor offers a few words of reflection, noting that his students used to be wonderful poets. Now though, they no longer write. While it goes unsaid by the professor, the implication of his comments is clear: his students left behind the “impractical” and “useless” pursuit of poetry for the “practical” and “useful” pursuits of business and monetary gain. What better place for these young and upwardly mobile students to be in than a fancy western dining room?

When the group stands for a toast to celebrate the professor, we get another strong hint that the way chosen by these young students is not the only one available to them in China. In the doorway pass four people—two musicians heading to their instruments, and two dancers donning traditional performing makeup and robes. As the traditional Chinese music begins to play, it stands as a complement to the scene behind the chatter around the table.

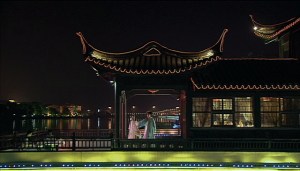

Jia uses a straight cut to shift to the next shot, which lasts just over 30 seconds. Now we see from outside the building, looking in at the dining room through the windows. The traditional music continues to play. Instead of a stationary camera though, we get a tracking shot, at first drifting slowly to the right before centering on the windows and the dinner party. Now the people are much less visible, generally only their heads popping up above the bottom of the window frames. Most obvious in this shot is the outside of the building, which is clearly a traditional Chinese structure. The criss-cross patterns in the windows are the biggest clue at this point. This traditional building was also suggested in the previous shot, as decorative eaves dropped into the shot from the top of the frame. We see then a group largely composed of people who have embraced the new modernity in China, yet despite their best efforts to surround themselves with western fineries, find themselves enclosed in a traditional world.

At this point, the camera begins to track back to the left along the buildings wall. Just as the shift takes place, we see the shadows of the dancers across a thin red strip at the corner of the building. The camera moves, eventually dividing the new and the old world distinctly, as we see in the shot above.

But the camera doesn’t stop at the split, continuing on to frame the dancers under a traditional gazebo, with red columns to the left. The costumes and makeup become clear now, a woman in a pink robe and a man in blue. They move to the music, which continues to play from some other unseen place on the deck. However, as the eye drifts beyond the performers, we see a short iron or wooden fence dividing the platform from a body of water. Continuing on, we see quite clearly a large modern bridge in the background, lit with electric lights and with cars speeding across it in the night. Now the traditional has taken the foreground, while the modern sits cold and distant in the background.

Finally, Jia makes his final cut to a shot that lasts about 10 seconds. It’s a striking long shot, encompassing the entire building and deck area in the shot. The building is more clearly than ever now a traditional Chinese structure with the decorative roof and walls. At the right side stands the main enclosure, with the guests still enjoying their meal in the room. In the center are the dancers, in the open air but covered by the gazebo roof. And finally to the left, for the first time we see the musicians playing completely in the open air. In the background, we get a different kind of progression, from a large modern building at the left, to the bridge in the center, and finally the whole landscape blotted out by the traditional building at the right. And though these three groups are separated by strong vertical lines (columns and walls), they are all ultimately joined by the yellow strip striking across all three areas below.

What we see here then is a beautiful illustration, both through the narrative and dialogue, and especially through Jia’s refined visual sensibility, of the complex relationship between tradition and “progress.” “Progress” seeks to move beyond the constraints of tradition; to either set aside or build upon the old in favor of the new. Yet Jia shows us here that even in humanity’s best attempts to progress, we still find ourselves surrounded by tradition, borne out of it and drawn back to it, however briefly.